Left: Colleen "Cosmo" Murphy, David Mancuso and me in Florence, June 23 - 2001

Right: David during the soundcheck at Red Zone, Perugia, April 20 - 2003

"The record is contemporary live music, while live music repeats, as dead, that music which was born from the record. So those who want to listen to some live music can listen to a record." - Manlio Sgalambro, 1998 - The Song Theory

"I'm just part of the vibration. I'm very uncomfortable when I'm put on a pedestal. Sometimes in this particular business it

comes down to the DJ, who sometimes does some kind of performance and wants to be on the stage. That's not me.

I don't want attention I want to feel a sense of camaraderie and I'm doing things on so many levels that, whether it's the

sound or whatever, I don't want to be pigeonholed as a DJ. I don't want to categorised or become anything. I just want to be.

There's a technical role to play and I understand the responsibilities, but for me it's very minimal. There are so many things

that make this worthwhile and make it what it is. And there's a lot of potential. It can go really high." - David Mancuso

I met David Mancuso in Florence in June 2001, thanks to her friend and protègè Colleen Murphy, who invited me to a party held in the

florentine hills. I remember that trip to Italy represented for him the opportunity to search for information on its Italian origins.

I also remember that the audio engineer on duty, after a long afternoon spent with David to calibrate the system, was surprised

that Mancuso had with him the pink noise on vinyl, which to me to be honest it seemed not so weird. He said to me in

neapolitan "chistu tiene o' rummore rosa su elleppì..." (this guy has pink noise on LP...).

That night along with other occasions spent with him, really was an experience. David shared with me many interesting stories

and technical aspects. He was really a lovely person. Meeting, after so long, the one I thought was the

basis of my passion and what we were doing in Perugia was truly memorable.

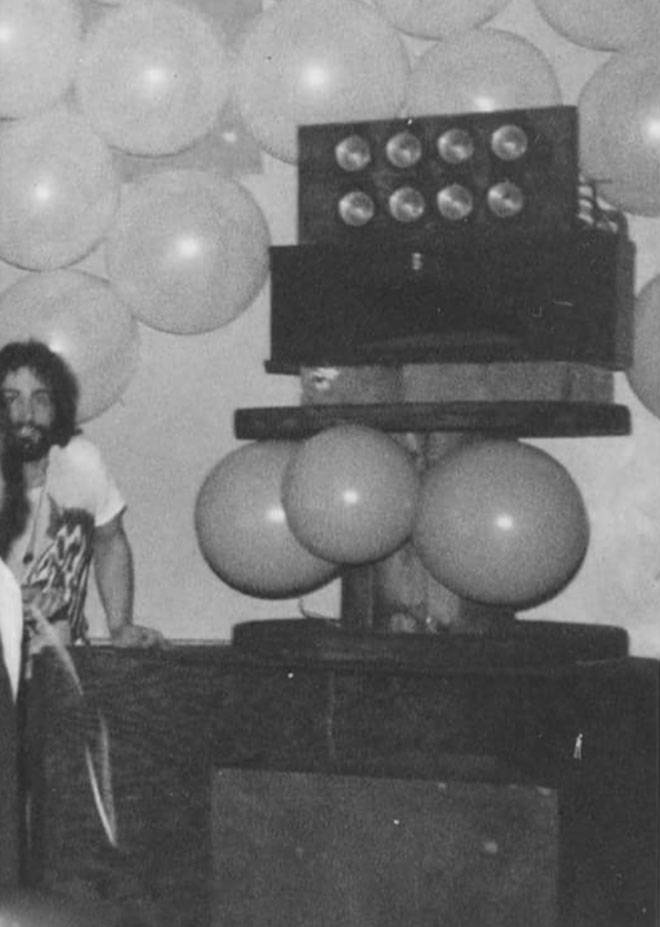

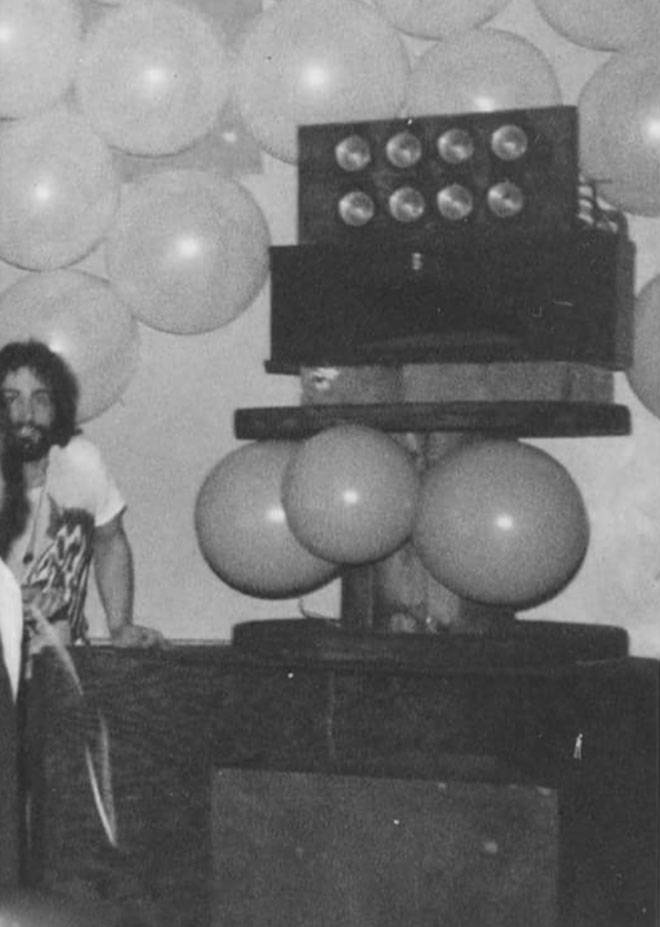

David Mancuso is the true pioneer of the modern clubbing. In the 1970 Valentine's day he started throwing after-hours

parties starting around midnight in the loft where he lived at 647 Broadway in NYC. This baloon filled party space became

know simply as The Loft. The Loft wasn't too big but it had a great domestic hi-fi sound system and Mancuso had the

musical direction based on his early psychedelic background and love for the black music.

Mancuso bought his first Klipsch "Klipschorn" loudspeakers for domestic purpose from Richard Long (RLA) before he went on

audio business in 1964. These loudspeakers were the personal ones which Long used at home.

In 1965 Mancuso moved to a loft in Broadway. In 1966 he started throwing private parties using two Klipsch "Cornwall" powered

by McIntosh amplifier and preamplifier. The sound sources were a Garrard turntable and a Revox 10 inches reel-to-reel.

In 1970 Mancuso starts giving rent parties. The fist called "Love Saves the Day" was held in Febraury 14.

The sources were two AR (Acoustic Research) turntables switched from one to another using the preamplifier.

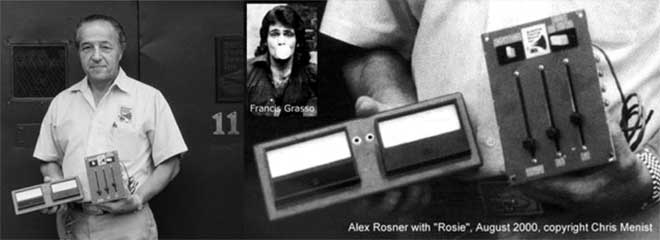

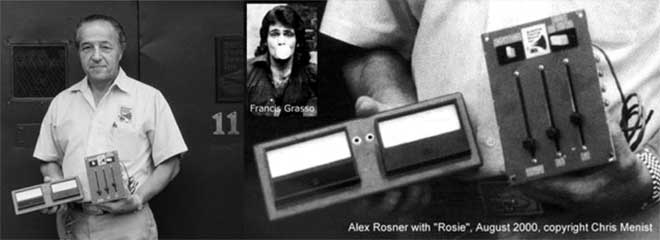

Alex Rosner with the "Rosie" mixer and Francis Grasso

Alex Rosner (Rosner Custom Sounds) constructed his first sound system for the Canada-A-Go-Go and Carnival-A-Go-Go stands at the 1964-5 where

he built the world's first stereophonic sound system. "Up until then it had all been mono. There was no equipment

available at the time. There where no mixers, no stereo mixers, no cueing devices. Nothing" he remember. Rosner moved in the clubs,

firstly with a place called Ginza and then with the Haven, where he built the "Rosie", the first ever stereo disco mixer used

by DJ Francis Grasso. "They called 'Rosie' because it was painted in red. It was really primitive and not very good. But it did the job.

And nobody could complain, because nothing else around".

Rosner sold to Mancuso the two Klipsch "Cornwall" loudspeakers for his space in Broadway back in 1966.

In 1972 Mancuso had the idea of improving the high frequencies at The Loft, then commissioned

to Rosner the building of two JBL tweeter arrays consisting of eight tweeters each, controlled by an active crossover.

"I pooh-poohed and said that it was too much. David replied, 'Never mind what you think. Just make them for me!' ".

Rosner mounted the tweeter arrays hunging them from the ceiling. "The sound was magnificent,"

remembers Rosner, switching into ironic mode. "So I said, 'Gee, it's a great idea! I'm glad you listened to me!' ".

The system was also tuned using Vega bass-horn speakers with the help of Richard Long who built a second active crossover

for them. This concept of splitting delegated speakers to the reproduction of certain frequencies will set a

precedent in the history of the club sound sytems. This was also the first attempt for Richard Long to go on the field of the audio business.

In 1973, two Klipsch "La Scala" were added as mid-side channels in the middle of the room.

The Loft moved at Prince Street 99 in November 1975.

The space was distribuited over two floors. The atmosphere was less intimate than Broadway, but Mancuso was determinated

to take his sound system on a new level of purity. When first moved to Prince Street new location, Mancuso continued to buy

equipment from Alex Rosner.

In 1978 Mancuso discovered from his close friend Harry Muntz, the sound of the Class A equipment.

He started buy high-end audio components from Lyric Hi-Fi, a local audio boutique, changing and experimenting by positioning

several "Klipschorn" loudspeakers, trying different amplifiers and turntables.

After several tests, Mancuso got a pair of Koetsu moving coil cartridges: a state-of- the-art hand made stylus by japanese artist swordsman and

hi-fi enthusiast Yoshiaki Sugano and two "B-1" turntable bases by Mitchell A. Cotter with Fidelity Research "FR-66" tonearms.

The sonic experimentation continued with the purchase of a Mark Levinson ML-1 preamp and ML-2 power amps.

Mark Levinson personally - described by Mancuso as the Walt Disney of audio - build a customized preamplifier that enable Mancuso

to hear every nuance of his recordings. Mancuso also wants to design his own equipment like a mixer without tone controls and frills.

He asked to his friend Harry Muntz - the man behind Richard Long according Mancuso - to build an audiophile stereo preamp - mixer which wasn't available on the market. When Muntz asked Mancuso to choice the type of controls for it - sliders or knobs - he chose the rotary knobs: " Sliders just go up and down whereas knobs are like a dance.

I went for the dance" says Mancuso. The final mixer was awesome but too expensive for marketing.

At that time, it sounded much better than any other.

In 1988 Mancuso discovered more about the influence of a minimalistic approach to audio world, keeping the electroacustic chain as simple as possible, and at the same time, learning more about physics and fundamentals of sound.

Mancuso is also the co-founder of the first contemporary "record pool", the system that distribuite promotional records to DJs while collecting feedbacks and relaying it all back to the music industry. He started at Prince Street Loft location in 1975 with Steve D'Acquisto

and Eddie Rivera. After the record pool official closing, the reputation of the Prince Street's Loft starts to increasing and the rent

as well. This was probably the most popular period of Mancuso's venue and he wouldn't think twice about improving the sound.

It was during this period that Mark Lewinson called the owner of Mancuso's favourite hi-fi shop to ask who spent the unprecedent

$150.000 on his audio equipment. Levinson visited the Loft as Mancuso remember: "He thanked me and I thanked him.

He walked gently away and stayed around for a while. He loved the whole idea of the party and seeing his work being put to a

positive use. It was a very important moment."

David Mancuso from an interview in early 90's.

Who made you want to be a DJ?

My mother had some difficulties when I was born, so I was put into an orphanage. There was one nun who used to look

after us kids, sister Alicia. She would find any excuse to have a party. She'd get breakers of orange juice for us and stack

a great big pile of records on the record player. There were these little tables and all the kids used to sit around them.

I don't know if you've ever seen my invitations, but there are all the kids sitting aroud a table on them too. I have a felling

that part of my influence for The Loft - why it was communical, why I did it the way I did - has to do with that time back then.

Did sister Alicia ever come to any of your nights?

No, she was very old by then. But I think she'd have enjoyed them.

Do we detected a religious influence, then?

First of all, music came before the word; music is s gift from gods. Music is a very powerful force for healing. When everyone

in the room is in the same place you get to a psychic level, you know what I mean? You can't explain it. There's a higher level,

a higher power. I'm not preaching or anything - this is about music.

Blimey. But you never mix records. Why?

The mix isn't as important as the song. As a DJ, you're painting something. The beauty is in the sequence and the narrative,

the story you build: the whole picture. I try to be a humble person, shedding my ego, respectig the music.

I'm only there to keep the flow going.

Are you flattered by the imitations The Loft has spawned?

Yes. Bacause a lot of people want to party. It's a positive thing: the more people partying the better it is, the easier you

can get through the week. It was like the civil rights movement: the more people you had marching, the better it was.

The way play now you could almost play with one turntable, has that always been the way you played?

No, I went through the whole thing, with mixers, not to pat myself on the back, but I was experimenting, I did not know

what I was doing, but tweeter and bass reinforcement was all originated from Broadway, it was developed there.

No, the commitment is there because I'm not a musician, I don't play any instruments, but I have the utmost respect

for the musician and for what his intention is. On the playback side, which is where I am, it must come through unobtrusively,

without any effect on the original intention of that recording. In the beginning I used to mix and the one mixer that I had

designed became the format of many mixers for years to come and things like that, bla bla bla, but that's not how

I planned it, things just grew. But I outgrew that, because the last thing in the world I would want to be is a disk jockey.

All I am is a player in this whole thing. It really doesn't matter. I see myself as an equal with everything, it's like we all play

in the same band, it's musicianship, whether it's somebody cooking in the kitchen, somebody dancing, doing this, doing that,

hanging up a coat, it's all part of the events that's happening. My responsibility is to make sure that at least on the technical

side that the record goes on and that it goes as smoothly as possible. And it was tough, because I used to be very busy,

with this, throw sonud effects in, this that bla bla bla. To go down to one knob, actually two knobs, Phono 1 and Phono 2.

Come to think of it, before there were mixers that was how we used to do it, go from phono one to phono two. So I ended

up going all the way back to that, because it's the cleanest way I can do it.

When did you decide to go back to basics?

When I started hearing the differences, first of all in the quality. When I really started to shed my ego in what I was doing.

I don't interfere with what's happening. It was at Prince St., and it was about the time I started to advance to class A equipment,

and I would say I was into my ninth or tenth year. You had to maintain a certain reputation, you had to stay, you had to be a

little too competitive with other people, these were my friends. I finally took the mixer completely out in 1984, 1985.

But once you start eliminating all these things out of the path in the playback, the more transparent the sound becomes.

So for me to hear all these nuances in the recordings - I know other people do too. I was amazed. I can't get in the way of what

the artist intended, I can't. I'm not happy. Not to say that if you're a disk jockey that's what you do.

What's the history of The Loft?

I was at Broadway and Bleeker and I started giving rent parties which basically it's still down to the same thing, to manage

and afford a life-style, that's basically the goal, to have a good time. From 70-74. Then the building got involved with a

dispute between the landlord and the tenants, I got caught in the middle and even though I've always been a safety nut

with two means of egress and so forth I didn't have a position for what I was doing, I don't know if there was a definition of

what I was doing anyway, but rent parties were legal. But I was living in a building that was lofts that you weren't really

supposed to be living in anyway, you picked up the beds, hid the refrigerator, you know, that kind of thing, but anyway,

I had to leave there. Well I didn't have to leave here,I had to stop what I was doing, and I moved to Prince street,

99 Prince Street, or else I'd still be there, I'm sure I'd still be there. It's interesting, it was a much smaller place, more intimate,

when I moved to Prince street it was like a gymnasium. I moved to 99 Prince Street, I was there for eleven years, and then I

moved to 3rd Street, got the building in 82, and in 84 I moved over. It was rough, I lost a lot of business, because in those days

people didn't go past 1st Avenue, 2nd Avenue. So that's it, 1 2 3.

What was underground music like in 1970?

Basically R&B, or what they called R&B. Anything that was danceable, it's hard to categorize individually.

The crossover music was there. Also there was the influence of stuff like the Stones, Led Zeppelin, Brian Auger, groups like that,

there was a good amount of crossover music, it certainly wasn't looked at as disco. [Then] disco happened. I think part of

what happened was the twelve inch came in. Deejays would take a record like Scorpio which has a nice little drum thing in the

middle, and take two forty fives and they would keep going back and forth and they would expand the time on the thing.

And that became the twelve inch.

David Mancuso taught us that being selfless is the ultimate act of rebellion

by Colleen "Cosmo" Murphy - November 2016

My close friend and mentor David Mancuso passed away earlier this week. I am devastated, as are thousands of other Loft

devotees. Some of them have met David, and some of them haven't, but all have been irrevocably affected by his approach

to music, sound, and the community spirit instilled by his parties. He changed the lives of so many.

My husband and I were with David Mancuso in Moscow for a few days in 2006 during the Iraq War. While we were waiting

in the lobby of our luxury hotel, looking and feeling somewhat out of place, a motorcade of cars pulled up to the entrance.

Out of one of the more inconspicuous vehicles emerged Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, whose security team swarmed

around her as she power-marched through the lobby. I looked over at David, who had a mischievous sparkle in his eye, and I

could tell he was up to something. Suddenly, he stood up and started shouting, "Love saves the day! Love saves the day!" over

and over again. She pretended not to hear.

David Mancuso was a rebel with a cause. But his cause did not revolve around the narcissistic, over-inflated, ego-led aims of

most DJs. In fact, David did not consider himself a DJ at all. His cause was informed by the ideals of the 60s counterculture,

and was concerned with respect, equality, love, and freedom. This may sound like reverent, outdated "hippie-speak" to a young,

contemporary audience, but I would argue that this set of values is not only defiant, but absolutely imperative in the face of the

growing right-wingism of the Western world.

David began hosting regular parties at his loft at 647 Broadway in New York City in 1970. He was a modest and introspective

man who was motivated by the civil rights movement, women's liberation, gay liberation, and class equality.

At his private Loft parties—which still take place to this day—people gather to dance and communally celebrate, irrespective

of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and economic class. David's aim was to build a community of like-minded souls and

to provide an inclusive safehaven where the only requirement was an open mind. In this era of social division, this is a very

daring concept indeed.

Of course, music was, and still is, the main ingredient and unifying force at the Loft. David selected the records, but he

considered himself a "musical host" rather than a DJ. He didn't want the adulation that so many DJs covet, and only put himself

forward to play the records because it was his home and his soundsystem. He felt his role was that of a musical conductor, that

he was channelling the music as an intuitive response to a telepathic conversation with the dancers. He once wrote me,

"Surrendering to the glory of music is a good thing." David hated the "Godfather of Disco" moniker that has so often been

bestowed upon him in recent times, not only because he did not want to be put upon a pedestal, but because he felt it was

inaccurate. David started playing records before the disco movement, and his long musical journeys— which often extended

over twelve hours—were comprised of soul, funk, R&B, psychedelic rock, jazz, dub, and anything else that worked within the flow.

These endless musical excursions had dips and peaks and were much more dynamic and emotive than the blinkered,

BPM-ruled, genre-specific DJ sets that are all too common in club music today.

Obviously, he did play records that are now viewed as important works of the disco canon. Many of these were first tested out

at the Loft, and then disseminated to other working DJs via The New York Record Pool—the first DJ record pool, which he

co-founded in 1975. There were also occasions where David's more esoteric musical choices became regional radio and club hits.

Sometimes, they even entered the national Billboard chart, as was the case with his championing of Cameroonian musician

Manu Dibango's "Soul Makossa," released in 1972.

But to David, the musical selections were just as important as the sound. He had always been inspired by the sounds of nature,

but it wasn't until he bought a couple of Klipschorns from soundsystem designer Richard Long that his unbridled and resolute

pursuit of sonic perfection began in earnest. In the 1970s, with the help of Alex Rosner, David put together a system that

surpassed that of any of his contemporaries, and which has stayed pretty much intact to this day. He spent an eye-watering

amount of money on multiple Klipschorns, Mark Levinson amplifiers, Mitchell Cotter turntables, and handmade Koetsu

cartridges—audiophile sound equipment that achieved the sonic purity David desired.

For him, the purity of the sound was about relaying the message of the music in the way the artist intended, unsullied and unmixed.

He often told me, "The sound of the music should be the dominant factor, rather than hearing the soundsystem." The Loft sound

set-up was widely regarded as the best by his DJ peers like Francois K and Larry Levan and dancers alike.

Producer François Kevorkian—who is known for his impeccable sonic mixes—recently wrote that he would "go into the studio

and pretty much do certain things to a mix because [he] knew they would sound so good on the system at the Loft."

It was through sound and music that David and I grew close. I started attending his Loft parties on East 3rd Street 25 years ago,

when I was 23, and after a few months, I mustered up the courage to ask him to play records on my radio show, Soul School,

on WNYU. He asked if we could have a chat first. We went out for a drink and discussed the synchronicity and nonverbal

communications a musical selector could have with a dancer, or in my case, my radio audience. We hit it off not only on a

musical level, but a spiritual level as well.

He came up to my radio show, marking the first time he had played records outside of his home. Soon after, in 1993, he invited

me to play some records with him at the Loft. Strangely, he didn't school me on the ins and outs of his soundsystem; he trusted

me to handle his Koetsu cartridges that retailed in the thousands of dollars. Decades later, after an intense audio mentorship

with him, I asked David why he had entrusted me with his set-up so many years before.

"It starts with a vibe long before one hits the turntable," he replied.

After the first time I played records at the Loft, he would often ask me to co-host on the turntables, and sometimes to fill in

for him in his absence. When I made the move to London in 1999, he and I put together the David Mancuso presents the Loft

compilation series for Nuphonic. Once in London, we teamed up with our friends Dr. Jeremy Gilbert and Tim Lawrence

—author of Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture 1970-1979, much of which is centered upon

David and the Loft—to establish The Lucky Cloud Loft Party. David helped us source the sound system for the quarterly party,

and musically hosted it until he retired from playing records for good.

So began another phase of our relationship, as David taught me about the hi-fi components of the Loft-style soundsystem that

Tim, Jeremy, and I had bought: the efficiency of horn speakers, speaker placement, delays, phasing, turntable setup,

cartridge tracking force, psychoacoustics. The list goes on and on, and I have emails and handwritten notes that should

eventually be collated.

He also passed on lessons about social behavior patterns and how to enable people to self-govern themselves in a party space

—spiritual and social teachings that stand in direct contrast to the primary focus of most clubs, which is to sell drinks.

Rather than adhere to the conventions of the commercial club business, David saw the party and dance floor as a sacred place

where people could "let it all out."

But the most amazing thing about David is that he wasn't proprietary about his knowledge. He wanted to share it and pass it on,

as he had a vision for the Loft to endure after his demise. My last phone conversation with him was this past Sunday, a few days

before he passed. Along with many other future plans, he reiterated his idea of creating a Loft Foundation, which he wanted a

select group of us to incorporate. He felt the Loft was not about him, but that he was the caretaker, and that he had prepared

some of us to carry the torch.

Without a doubt, David changed our lives. Even more significantly, his spirit lives on through the continued Loft parties in

New York, and as well as direct descendants of it that have been blessed by David: the Lucky Cloud Loft Party in London,

Last Note in Rome, and Satoru Ogawa's parties in Sapporo, Japan, which use a nearly identical sound set-up to the Loft.

I hope, and believe, that the Loft parties and spirit will continue after our generation of Loftees and Loft caretakers pass to

the next realm. Only somebody who is selfless can orchestrate that. And in today's age of perpetual self-promotion,

being selfless is about as rebellious as you can be.